By Clément Miège

Hi there! I am Clément Miège, a Ph.D. student at the University of Utah and I am going to take you along with us to our second expedition to the southeast region of Greenland, to investigate the physical properties of a firn aquifer. And what is a firn aquifer, you might be wondering? It’s a reservoir of perennial water (that is, water that doesn’t freeze in the winter) that is trapped within the compacted snow layer (or firn) of the Greenland ice sheet. If you didn’t follow last year’s edition of this expedition and/or you want to learn more about the firn aquifer, here are some readings I recommend:

- Our team’s blog posts from last year will give you some background material on the set-up of the expedition and work over the ice sheet. It describes the travel to our field site in Greenland and the techniques we used on the ice sheet to do a first measurement of the volume of water within the firn aquifer.

- To complete this story, my team and other researchers recently published a journal article where we described how this aquifer was serendipitously discovered in the spring of 2011 when we were sampling regions of high snow accumulation. The paper also describes how we first mapped the aquifer using a combination of firn cores, ground radar and airborne radars.

- Finally, we published another journal article following up on the blog posts from last year and determining the volume of the water trapped in the firn aquifer at a specific location. We obtained this volume by comparing the mass of a wet firn core taken inside the aquifer to a core taken in an neighboring area of dry snow. If you assume this water volume is constant throughout the entire firn aquifer (which spreads over an area larger than Western Virginia!), that would correspond to 140 gigatonnes of water stored. To say it in a different way: if the water runoff the ice sheet, it would raise sea levels worldwide by 0.016 inches (0.4 mm).

- And if you don’t feel like reading scientific papers right now, NASA put out a story about our findings, too.

We are now getting ready for another expedition to Greenland to further monitor the firn aquifer. This year, our four main tasks will be to maintain our equipment currently in place (which performs temperature measurements), collect additional measurements (with a radar), install a weather station, and try traditional ground-water techniques to date the water and calculate its permeability. I will explain in future blog posts why these measurements are important.

I will be part of a smaller team this year, since only three out of the five members of the first-year team are joining. Rick Forster and I will represent the University of Utah, while Ludovic Brucker comes from NASA Goddard Space Flight Center.

Here is the photo of the team from last year, from left to right; Jay, Ludo, Rick, Lora and I. Lora and Jay won’t be coming to the field this year (we sure will miss them!) If you want to know a bit more about each team member (current and former), you can check this blog post from last year.

Even when we haven’t set a foot in the field yet, the expedition to Greenland started about two months ago with organizing the logistics. Logistics can sometimes be underestimated, but it takes a lot of effort prior to getting to the field to prepare and test the scientific equipment and other field supplies, such as camping gear, food, and power sources.

For this expedition, all of the science equipment (GPS, radars with different frequencies — 5MHz to 400MHz–, piezometers, ice-core drill) was gathered from different institutions in Utah to be packed here and shipped to Kulusuk. Most of the non-perishable food and camping gear was left for over-winter storage after last year’s expedition in a warehouse in Kulusuk, to save on shipping costs.

On March 3 this year, the Utah gear left for Greenland; we’re talking about 800 lbs. of gear that left Salt Lake City on a truck headed to the JFK airport in New York, where it was flown to Reykjavik (Iceland) and then to Kulusuk (Greenland). We got a phone call early this week from our shipping company to confirm that all our equipment made it to Greenland — great news!

Gear packed at the office (left) and ready to leave the shipping facility at the University of Utah (right). We will see this gear again in Greenland!

These last days have been really busy, gathering the last items for our science research, and also personal equipment. Yesterday, I was working at Blue System Integration in Vancouver, BC with a colleague, Laurent Mingo, who is developing IceRadar, an ice-penetrating radar system for the scientific community (see this website for additional info). Laurent has been working on an experimental beta version of the current radar that will allow us to penetrate through the firn aquifer to try to image the bottom of the aquifer gradually transitioning from water-saturated firn to ice.

Even if most of the scientific equipment is already shipped, there are always some last-minute important items that we end up adding into our suitcases (like the low-frequency radar). As a brief anecdote, last year, Rick traveled with a pelican case as a checked bag – inside, there was a bunch of wires hooked up to a datalogger. We were aware that it looked kind of suspicious, so it was a bit scary to go through customs with it! Me, I traveled with a 60-meter long thermistor string weighing over 50 lbs. in my checked bag, because the fabrication and calibration took longer than expected and we weren’t able to ship it ahead of time with the rest of the equipment. This year, luckily, most of the heavy equipment was ready on time and we are carrying only a couple random items in our checked bags.

We are starting our journey this week, leaving the U.S. on Thursday evening for Reykjavik, the capital of Iceland. After a day in Reykjavik, we will leave mid-Saturday on a 2-hour short flight that will take us to Kulusuk, Greenland. We are hoping for good weather; last year, Ludo and I “boomeranged” on our first try due to poor visibility at the Kulusuk runway.

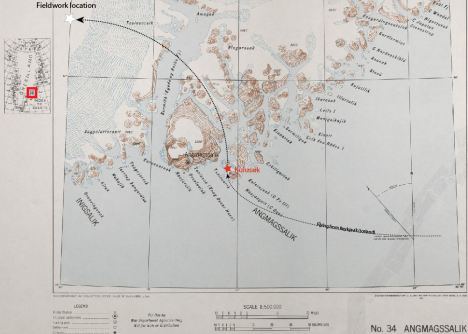

In this old map from the US army (from 1941) you can see the location of the small city of Kulusuk in Southeast Greenland (red star), just below the Arctic Circle (~66.5°N). Our field camp on the ice sheet is represented by a white star. The map can be found at the Polar Geospatial Center.

Kulusuk is our first stop in Greenland. We will be staying at this small village for a few days in order to re-pack our field gear, test that everything is working well (stoves, generators, tents, science equipment, etc.) before going to the field. If we are lucky, we might see one of the polar bears that sometimes come close to town in this time of year.

Colorful houses make up the town of Kulusuk in Southeast Greenland. The shores of the fjord are covered by sea ice in the winter.

After a couple of days, we will be heading to our fieldwork location on the ice sheet. A helicopter from Air Greenland will drop us and our cargo at our study site; it will be an about 45-minute commute.

That is it for this introduction; our next blog post will be from Greenland!

All the best,

Clément

Tags: aquifer, Arctic, climate change, cryosphere, drilling, Greenland, NASA, polar science

Good luck and try to stay warm!!

Very excited to be following your expedition and reading the blog, looks fascinating good luck and be safe!

Good luck Clement! Hopefully the weather station made it in time from Utrecht to Kulusuk.

How exciting Clement! Your current location in SE Greenland is one that I have been studying to visualize for over a year. Presently it is a cartographic illustration on a 60″ high by 72″ wide canvas. Until now with your first actual photographs and old Army Map #34 I have been describing an elephant without ever having seen one.

Thank you and may the gods be with you all.